This article is part of our series on responsible mining solutions. The push for clean energy is fueled by growing demand for minerals, but conventional mining has a history of harmful social and environmental impacts. The use of blockchain traceability tools could be part of the solution to this problem.

Minerals change hands several times as they move from mine to smelter to manufacturer. When they reach the company that makes auto parts, battery components or solar panels, no one really knows where the minerals come from.

Not knowing the origin would not be a problem, except that some mines operate using child labor, forced labor, environmental neglect or without any legal status. In some regions, the extraction of minerals such as tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold also provides an important source of income for violent armed groups, giving rise to so-called “conflict minerals”.

Although some companies don’t care, most are unwilling to support illegal and inhumane mining operations. But it’s not so easy to know for sure that the minerals don’t come from problematic mines.

One way to prove the origin of minerals is to create an authentic record of documentation for each stage the minerals go through, from mining to manufacturing, and blockchains are emerging as an efficient place to house this information.

From crypto mining to traditional mining

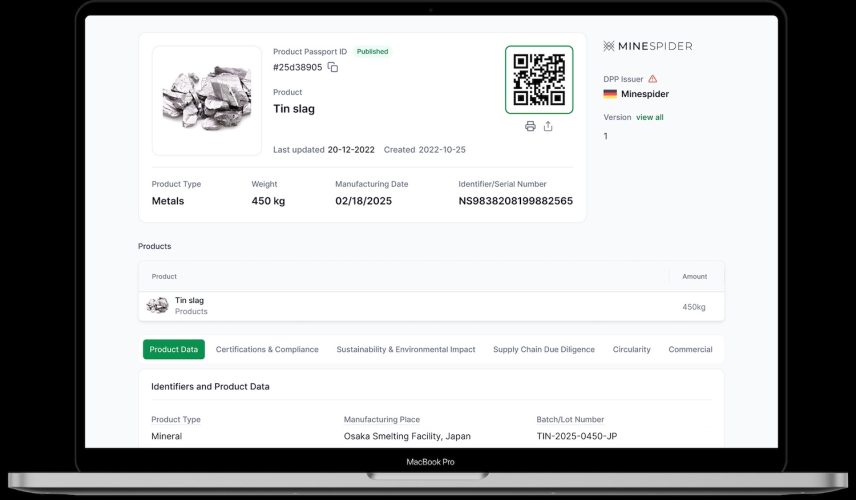

Based on the same system that records cryptocurrency transactions, blockchain tools can be adapted to track mining transactions. Documents proving origin, sales, transportation, certifications and audits can all be uploaded digitally to tell the story of a mineral. Then, QR codes attached to sealed bags, boxes or shipping containers can directly link to this information.

“The main advantage is that blockchain allows you to have immutable data,” said Nathan Williams, CEO of Minespider, a company that provides blockchain solutions to the mining industry.

When something is uploaded to the blockchain, it stays there forever and cannot be changed. Information can be added, but each addition comes with a timestamp and a record of who added that information. In this way, mining transactions become completely transparent as they occur downstream of the mine.

It’s important to know where minerals come from and how they changed hands along their journey, but that alone doesn’t tell you about conditions in the mines. If mines are certified and audited for responsible management and humane labor practices, documents verifying this can be uploaded to the blockchain, providing assurance that minerals are responsibly sourced and due diligence requirements have been met.

Because some raw minerals come from mining, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has created due diligence guidelines to help companies ensure their supply chains are not engaged in abusive practices. The European Union has written corporate due diligence requirements into law through the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, with mandatory reporting expected to begin in 2027. And the US and EU both have regulations on conflict minerals.

Rwandan tin smelter runs on blockchain

Tin is one of the main conflict minerals along with tungsten, tantalum and gold. To assure buyers that its tin is conflict-free, a Rwandan foundry has implemented a series of solutions, one of which involves blockchain traceability tools.

“Tin is classified as a conflict mineral, so we need to put all our traceability protocols in place,” said Aleksandra Cholewa, director of investments and development at Luma Holding, the company that owns the Rwandan tin smelter.

It all started by becoming the first African tin smelter certified by the Responsible Minerals Assurance process, which is the gold standard for due diligence monitoring for smelters around the world. The process certifies that smelters are responsibly managed and conduct due diligence on their supply chains that meets the requirements of OECD guidelines as well as regulations in Europe and the United States.

Luma wanted to go further, however, and track exactly which minerals came from which mine.

“We have about 30 different suppliers in Rwanda. We have successfully implemented blockchain traceability at each of these mining sites,” Cholewa said. “We started issuing digital product passports for every tin shipment in December 2020. And through this, we also managed to attract new purchasing customers, those who were previously very hesitant to touch anything from this region.

The process is different at each mining site, but imagine a small-scale mine where workers fill bags by hand with tin ore. Once filled, the bags are assembled for transport. The bags are numbered, weighed and sealed before being placed on the truck. All of this information is documented with photos, written records, and logs, then uploaded to the blockchain with a timestamp and a record of who added the information.

Using a QR code or other form of digital access, when the mineral shipment arrives at its destination, new documents confirming its arrival can be added to the blockchain. This process can continue as many times as necessary, providing a robust digital product passport.

“It’s a great way for our customers to prove to their authorities or customers where the product came from and what kind of journey it took,” Cholewa said.

Katie Redmond, technical director of audits and mapping at SLR Consulting, which specializes in sustainability, echoes the buyer trust effect of blockchain. “Digital traceability tools can be useful for mapping supply chains based on supplier-to-supplier connections and giving companies confidence that they have performed required due diligence on their subcontractors,” she told TriplePundit in an email.

Blockchain tools can be applied to large-scale mining or artisanal and small-scale mining. But one of the challenges of artisanal mining is that the informal nature of the sector can make it difficult to obtain the right documents and pay for the blockchain solution to be implemented, Minespider’s Williams said.

One tool among many in the due diligence toolbox

An additional challenge of working with blockchain tools is that they are often proprietary, meaning that combining two different minerals from two different blockchains into a single final digital product passport can be tricky.

“A risk with multiple proprietary systems is that definitions and data formats are not comparable or consistent,” said Jennifer Peyser, executive director of the Responsible Minerals Initiative, the organization that developed the Responsible Minerals Assurance Process certification. “Suppliers can also face significant constraints when asked to use many different systems or software. »

Blockchain does not solve all supply chain problems, but it is one tool in the due diligence toolbox. Supply chain partners must always have strict due diligence procedures in place to ensure that minerals are responsibly sourced and are not mixed with minerals of unknown origin.

“The idea here is that you’re looking for data that helps you avoid risk,” Williams said. “Technology enables data, but it is not a substitute for due diligence. It is meant to facilitate due diligence.”